Elephants sowing seeds for future

November 2nd, 2014

Lindsay Brooke joins researchers on a field trip in the rainforests of Malaysia.

“There’s one!” We have been out all night in the Malaysian tropical rainforest searching for elephants and now, at four o’clock in the morning, we get our first sight of one.

Researchers from MEME, the Management and Ecology of the Malaysian Elephant, together with Perhilitan, Malaysia’s Department of Wildlife and National Parks, are fitting wild elephants with specially designed collars packed with satellite and cell phone technology. The aim is to learn more about the Asian elephant, and crucially how to mitigate the growing problem of human-elephant conflict. I have been invited to join MEME on a field trip: it was to be a remarkable three days.

Hunted for their tusks and stripped of their natural habitat to make way for crops, roads and new settlements the Asian elephant is listed as endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

What becomes of these elephants and the effect that will have on the ecology of Malaysia’s rainforest is the focus of MEME’s research. The work requires time, personal sacrifice, diplomacy and, as I was to discover, long hours of what can often prove to be unrewarded effort.

Four hundred kilometres north of Kuala Lumpur, close to the Thai border in the state of Perak is the Royal Belum State Park. From here we took a boat across the vast Temenggor Lake to a place where wild elephants come to take minerals from the ground. This ‘salt lick’ is deep in the heart of the Temenggor forest – claimed to be one of the world’s oldest tropical rainforests. When they come here the elephants are photographed and filmed by a set of automatic cameras strategically placed in the trees around them.

The pictures are critical to MEME’s research, which is being led Dr Ahimsa Campos-Arceiz from the School of Geography at The University of Nottingham Malaysia Campus (UNMC).

Dr Campos-Arceiz said: “This is a very personal kind of project. It is something we believe in and the work fulfils us. MEME is acutely aware that the Asian elephant is in trouble and its distribution is shrinking. We want to contribute to the long-term conservation of Malaysian elephants and the best we can do is to obtain scientific evidence to help the government make better-informed decisions. Ultimately, we’ll need to find ways for human-elephant co-existence in these landscapes.”

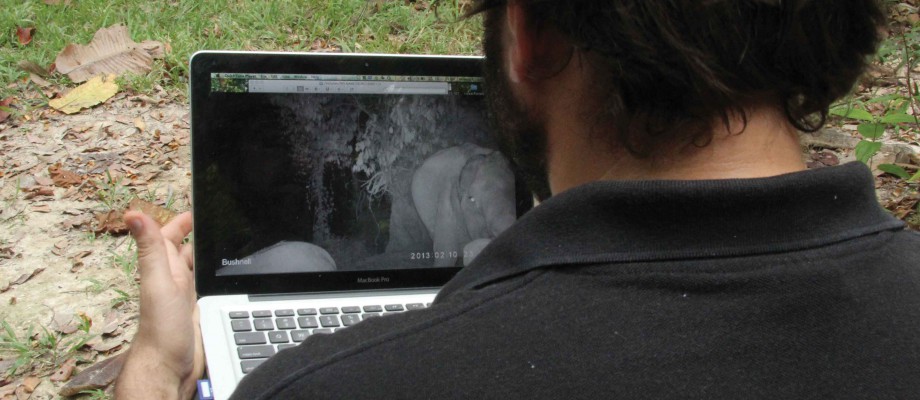

Eager to know what secrets the cameras hold, Ahimsa is soon uploading the files to his laptop. He’s delighted to find that elephants and a couple of rarely seen Sun Bears have trouped past, triggering the cameras. The pictures give MEME a unique insight into the social structure of the Asian elephant. They can also assess the health of the elephants.

Our next stop is the site of a sulphur spring, where animals visit to drink essential minerals dissolved in the warm bubbling water. The elephants leave behind enormous piles of dung. Everyone is put to work sifting through each and every pile looking for seeds. If it is really fresh the dung is checked for parasites and samples are taken for DNA and hormone levels which can assist in determining stress levels.

The elephant is a key biological species in the ecology of Asia’s tropical forests and plays a major role in the dispersal of seeds. It is capable of digesting some of the largest seeds in the forest, and across the forest floor mangos and other jungle plants sprout from old droppings. Checking the dung helps MEME learn more about the importance of the elephant and the role it plays in the ecology of Malaysia’s shrinking rainforest.

By early evening we are heading back to the field centre in Gerik, but our day is far from over.

Our journey is broken when we spot Awang S Kedah, the bull elephant tagged two days before. In broad daylight he gives us a rare opportunity to photograph and video him before he disappears from sight.

At 10pm two new collars have been loaded into the back of the MEME jeep and we are on the road again. It is the last night of collaring for a few weeks. We drive in convoy along one of Malaysia’s main highways using searchlights to scour the vegetation for elephants. Just before dawn an elephant is spotted. The convoy pulls up and a darting gun is loaded with sedative. Even though they’ve done this many times before, there’s still a sense of excitement at the prospect of recruiting another elephant into the MEME study.

But it isn’t to be. The elephant has gone. In fact, elephants prove elusive on six out of the seven nights. However, on one night alone they had managed to tag two elephants, including our friend Awang S Kedah, and that is more than good enough for Ahimsa and his colleagues.

There are now seven collared elephants roaming the Malaysian tropical rainforest. The aim is to have 50, providing what could prove essential information in the future survival of these animals and establish a balance so man and elephant can live alongside one another.

For more information about the work of MEME go to:

www.meme-elephants.org

www.facebook.com/MEME.project

Tags: Dr Ahimsa Campos-Arceiz, Lindsay Brooke, Malaysia, MEME, School of Geography, the Management and Ecology of the Malaysian Elephant, The University of Nottingham Malaysia Campus

Comments are closed.

Other Issue 72

Twins: business is in our blood

Inspired by their grandmother’s resilience in starting businesses during the Cambodian genocide of the 1970s, twins […]

A little of your time can go a long way

The University has helped launch a volunteering scheme in Nottingham which is aimed at professionals who […]