The University of Nottingham

Exchange online

Exchange online

Research Exchange

Leaving no stone unturned

As bucket lists go, Professor David Walker isn’t doing too badly. Already crossed off his list of personal highs are an encounter with the former South African president Nelson Mandela while in Norway for an academic conference and completing a gruelling 1,036-mile cycle ride from John O’Groats to Land’s End.

The same focused energy which fuels a passion for adventure has been a significant driving force behind the successes David has enjoyed in his professional life — successes which have helped to transform the outcomes of so many children and young people affected by brain tumours.

When he helped to establish The University of Nottingham’s Children’s Brain Tumour Research Centre (CBTRC) in 1997, awareness of brain tumours was scientifically and clinically at an all-time low.

Since then the centre has been instrumental in bringing the devastating effects of brain tumours into the national public and political consciousness, while delivering ground-breaking research which has radically improved our understanding of the biological mechanisms that cause the disease.

But as a fierce advocate for his patients and their families, David’s underlying focus has never wavered — his number one aim is always to guarantee the excellence of their care.

“I enjoy working with people who share vision and ambition and have plenty of energy,” he said. “Everybody at CBTRC is very motivated, which is one of the reasons I love coming to work. We make things happen.

“If you can say at the end of the day that you’ve done things to the best of your ability in very difficult circumstances, then that’s the ultimate goal. For patients whose disease is proving tougher than they are, to feel that we have left no stone unturned is extremely important.”

David discovered how rewarding working with children and families could be almost by chance — early on in his career he was considering general practice and thought a spell working in paediatrics might offer some valuable experience. It proved to be serendipitous and a move which would go on to shape the rest of his working life.

“I found I really enjoyed the relationships I developed with the children and their families,” he explained. “I had previously worked quite a lot with blood disorders and when I started treating children with leukaemia I found I already had an excellent grasp of the medicine, which was very rewarding; the two things just clicked. That’s the big difference between now and then in medicine: people’s careers evolved in those days. I didn’t have a clear vision of what I was going to be when I qualified so an experiential approach suited me extremely well.”

But it could all have been a very different story. David was born in Scotland and lived in the North East of England before moving to London where he was educated at Westminster School. He might have been expected to follow his father and older brother into the world of accountancy and business. Instead, he surprised everyone by contemplating a career in medicine.

He arrived at The University of Nottingham’s Faculty of Medicine in 1972 to a Medical School still in its infancy. Among the school’s third cohort, he was one of just 48 people on the course — the staff almost outnumbered the students. There was a sense of excitement in the air — the staff were enthused by the experience of designing the UK’s first new medical course for a century and keen to involve the students in educational debate and strategy. But it wasn’t all about academic endeavour; there were extra-curricular opportunities for the enthusiastic young medical students too during those early days. As President of the Medical Society, David was able to indulge his love of sport by helping to establish — and play for — the Medical School’s first rugby team.

David completed the course in 1977 and took his first steps in his career as a junior doctor at Nottingham’s old General Hospital. He was there for a year before moving to Addenbrooke’s Hospital in Cambridge for a post in haematology. This offered the chance to work with patients in the clinic but also to undertake research in the laboratory.

It was followed by spells at Leicester Hospitals, St Mary’s Hospital London and Sheffield Children’s Hospital, before a step up to the prestigious Great Ormond Street Hospital (GOSH) to work as a senior medical trainee in paediatric haemato-oncology.

While there he was given the opportunity to work for two years as a clinical research fellow at the Royal Children’s Hospital in Melbourne, which, significantly, had a particularly strong brain tumour programme. Also rather significant was the proposal of marriage to his future wife Gilly — made over the telephone from Down Under. She flew out to Australia to join him, although they returned to the UK to tie the knot.

“At the end of the two years I came back to work at GOSH for about a year and was asked to initiate a brain tumour national study group which discussed clinical trials and translational research. The group also wrote a document that named the children’s cancer centres and their associated neurosurgical centre, which meant that for the first time children were all being treated in centres with particular expertise for young people and that made a big change in the way that patients came to the attention of the specialists and improved the coordination of their care. That was how I really developed my career interest in brain tumours and it was shortly after establishing this study group that I found my way back to Nottingham and established the Children’s Brain Tumour Research Centre alongside Jonathan Punt, a neurosurgical colleague and senior lecturer.”

The CBTRC was formally launched in 1997 after The University of Nottingham agreed to fund it as part of the original Jubilee campaign — it is now one of the major projects supported by Impact: The Nottingham Campaign. The centre focuses its activity in three main areas. The first, led by Professor Richard Grundy, concerns developing our knowledge of the basic biology of brain tumours in children and young people – why exactly do their young, normally developing tissues become malignant when tumours are more commonly associated with mutations arising from ageing?

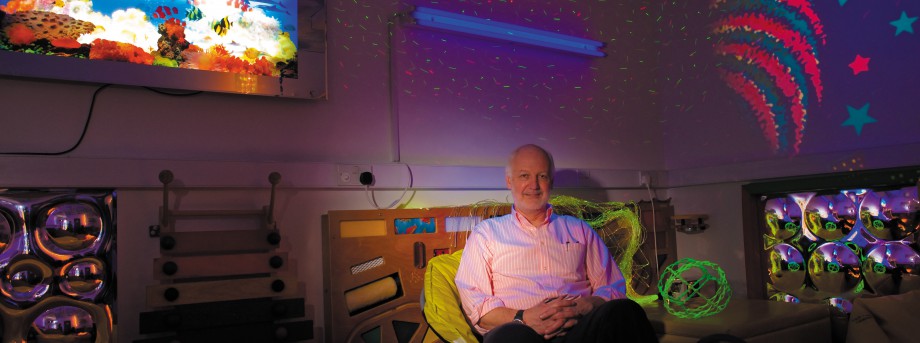

The second theme looks at drug delivery, in particular how to get the right drug into the brain to treat the tumour with maximum effect and the least side effects. The centre has a team of people working across disciplines — tissue biologists, research pharmacists, neurosurgeons and even mathematicians and theoretical scientists. The united aim is to get three new drug delivery systems into clinical practice within the next five years. They have made considerable progress on a novel process that uses the continuous infusion of the drug injected directly into the spinal fluid to cross the blood/brain barrier. Dubbed INTREPID – Intrathecal Etoposide – it’s an approach which no one has successfully done before. The centre will launch a nationwide trial later this year to test its safety and feasibility. Working with Professor Kevin Shakesheff’s group in the School of Pharmacy, the centre has also developed a biomaterial that could be used to deliver the drug directly to the brain tissue after an operation, while the third method of delivery is in the early stages of development.

‘Impact’ is a widely used academic term, but for the centre’s third research stream it refers simply to translational research: taking ideas into the health world and making them work. Probably the centre’s most notable impact project is Headsmart: Be Brain Tumour Aware (www.headsmart.org.uk), which aims to highlight the need for greater awareness of the symptoms of brain tumours to reduce the time people spend waiting before diagnosis. Since its launch in 2011, the campaign has been highly effective — symptom interval in the population of UK children who get brain tumours has reduced from just less than 15 weeks to just less than seven weeks and around 10 per cent of the population is now aware of Headsmart: Be Brain Tumour Aware. The campaign has received national recognition in the form of a NHS Innovation Award worth £100,000.

David said: “We don’t want to cause panic; we just want to make the public and the medical profession more fluent in spotting symptoms and to encourage them to take action when they recognise them. This year we hope to engage directly with the 46,000 general practitioners who are of course a very important part of this whole programme. That process has started already, not least because the GP who sits on our project board is now the president of the Royal College of General Practitioners, Dr Maureen Baker from Lincoln. A real stroke of luck for us — she even agreed to get involved without the need for the application of thumb screws!”

In addition, the CBTRC is studying the impact of different types of rehabilitation after brain injury and other chronic illnesses in children and young people of all ages. Finally, a new programme of research has recently commenced in the CBTRC to investigate the impact of surgical and tumour injury to the cerebellum in young children. This work is being carried out with the Nottingham Toddler Lab at The University of Nottingham and will analyse outcomes during development with patients recovering after tumour surgery.

Between caring for patients, research and the inevitable administration that comes with both you’d perhaps expect any recreational time to be spent largely in a prone position. But David prefers seeking out activities offering a personal challenge.

A fondness for hillwalking has led to the energetic pastime known as ‘Munro bagging’ – the quest to climb all of the 284 Munros, Scottish mountains with a height of over 3,000ft. During his annual pilgrimage to the Highlands, David has so far managed an impressive 187.

August 2011 saw him back north of the border to begin the 1,036 bike ride from John O’Groats to Land’s End with The University of Nottingham’s Vice-Chancellor Professor David Greenaway and his Life Cycle team raising money for research into palliative and end of life care, arriving at their Cornish destination in an impressive two weeks. He was back in the saddle again to join the VC and team for legs on Life Cycles 2 and 3.

“I think our Vice-Chancellor demonstrates outstanding leadership qualities under stress. To be with those who are prepared to share a physical challenge is quite an inspirational experience. The people I enjoy being around in my spare time are often a little bit like that — quite sane but with a different judgement on risk! I am naturally delighted that this year’s Life Cycle 4 effort will directly benefit the Children’s Brain Tumour Research Centre.”

This profile will be part of a research e-book set to be launched later this year. Follow @UoNresearch on Twitter

to keep up to date.

For more information on Life Cycle 4, visit www.nottingham.ac.uk/lifecycle

Tags: Children's Brain Tumour Research Centre, Impact: The Nottingham Campaign, Life Cycle 4, Professor David Walker, research profile

Leave a Reply

Other News

Top prize for quantum physicist

A University of Nottingham physicist has won a prestigious medal from the Institute of Physics for […]

Zero carbon HOUSE designed and built by students comes home

Design and construct a low cost, zero carbon, family starter home, transport it to Spain, build […]